The Creative Effort Interview: Nate Baranowski

In this conversation, I talk with 3D street artist Nate Baranowski as he walks through how an unconventional creative career actually works in practice. What started as a side gig getting paid to draw chalk in college grew to a global niche creating anamorphic illusions for brands, festivals, and public spaces. It might seem like something playful and ephemeral from the outside, but it requires deep discipline and an almost obsessive attention to perspective.

Throughout the interview, Nate shares his insights about creativity that apply far beyond street art. For example, he shares his thoughts on why execution matters more than novelty, why clients don’t want to stand inside advertisements, how constraints improve creative work, and how new tools like VR can fundamentally reshape a craft. The result is a grounded, honest look at what it takes to make creative work that actually connects.

This interview was lightly edited for clarity.

Listen to this interview: Spotify | Apple Podcasts | PocketCasts

Jason: Nate Baranowski, thank you so much for joining me, mostly for being my guinea pig. Let’s start with ‘what is the short version of what you do?’ And then we’ll spend the rest of the time kind of unpacking the longer version of that.

Nate: Sure. The short version is I am a street painter. I am a chalk artist. I am a 3D illusion creator on the walls, on the floors, and on the streets.

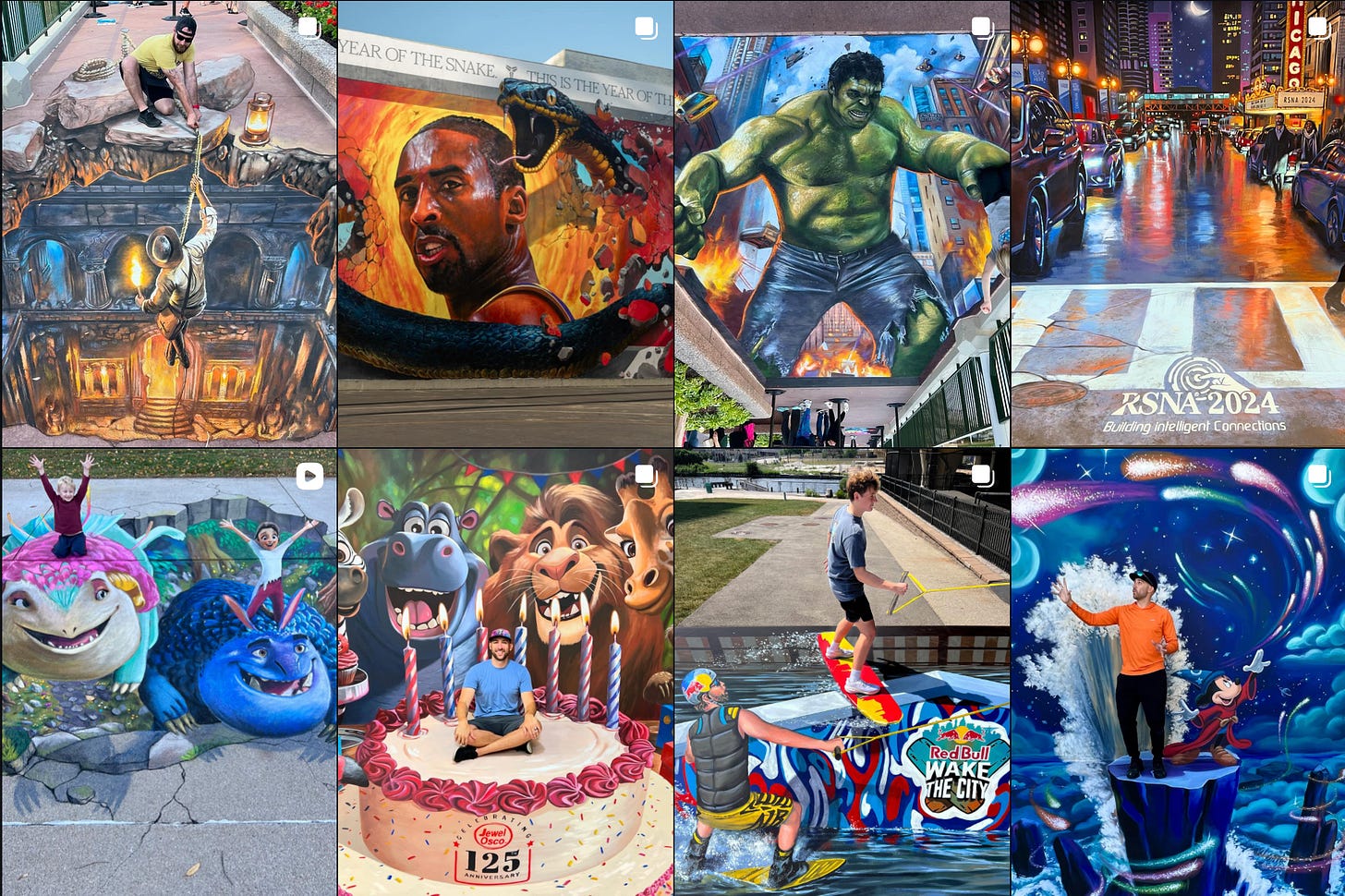

Readers, you might want to just go look at some of Nate’s work because the reason I picked him to be my first guest is that he is truly one of the most creative people I know. More importantly, he’s not the kind of creative person who sits in rooms and thinks creative thoughts—he makes very cool stuff. And so I definitely want you to go and look at it.

So, you said you’re a 3D street painter, chalk artist. What does that mean? On a regular basis, what are you doing?

What I tell both my extended family members at Christmas and clients is that I paint or draw in chalk so that, from one viewpoint, it looks like a 3D world. And so what I’m creating is meant—in a camera—it is meant to pop out of the ground or out of the wall. And people can pose in my art to become part of the illusion.

This form of art is super niche. And I think I know everyone who does it professionally in the whole world. Not just the US. Everyone who makes a living doing this, I think I know. So it is a very small world, but a very cool world.

Okay. I have so many questions. I’m going to try to stick to the script that I have. My first one is, how did you get started doing this? I know that that’s probably not a super short answer, but you said it’s such a very specific thing. There’s a very small number of people in the world who are doing this. How did you become one of them?

Well, for me, I’m going to give you the shorter version, which is that in college, I decided I wanted to make a little bit of money. So I had always drawn in chalk just in my driveway growing up. I saw a couple of chalk announcements in the quad at the University of Illinois, where I went to undergrad. And I saw people scrawling out messages. And I said, Oh, I think I could make a nicer version. And then if you pay me 20 bucks, I’ll be out there drawing and then putting a little picture next to whatever announcement you want to put there.

Fast forward from there to maybe five years later, I had lived in Milan, Italy for a short amount of time, and saw some people doing chalk art there, like busking, busking? I think that’s the right term, and making money just off of tips and doing chalk art on the ground.

And I moved to Tampa, Florida. And in Florida, it is chalk weather 365 days, and they started having chalk festivals all over the state of Florida around the time that I was there. And, while I was there, I started doing chalk festivals. Not 3D stuff, just ‘hey, I like this image, I’m going to create it on the street for two days.’ And, not get paid and then go back to my design job that I was working at the time

From there, that developed into oh people, and well, specifically clients, will pay. I remember helping out another artist doing a job for Pringles in front of a Walmart. We’re literally like right in front of a Walmart doing a 3D Pringles can, and I said, “Look, I got paid, this is great!”

So, advancing from there, I started painting some murals. But every once in a while, I would get a paid chalk art [gig] and build my portfolio until eventually I was comfortable and good enough in this field that clients started reaching out to me with “Hey, we see this viral sensation of chalk art getting spread all over BuzzFeed and the internet. Can you make something for our brand for this?”

And so that became doing more and more jobs until eventually I was doing basically 3D chalk art. Then that turned into 3D street painting because sometimes clients want stuff inside of a convention hall, and that needs to be in paint and not chalk. Or, we don’t want it to wash away with the rain; we want this to be in paint.

So all of that developed into, I have a knack for creating these 3D illusions, and I just kept rolling with it, and here I am now, probably have been doing 3D stuff for about 11 years.

You said two things I just want to ask about. First, you said you first saw this when you were in college, and then you said you went back to your design job. What was college like? I mean, I don’t think they have a lot of courses in 3D chalk art, so what did you study in college, and then it sounds like you were doing something creative when you got into this?

So my degree was in industrial design. I wanted to go for some sort of art degree. Thankfully, my parents were able to pay for college for me. But sadly, they said, no art degree. We will pay for it, but you can’t do something with just a fine art degree.

So I found industrial design, product design, and I went into it with the idea that I wanted to learn how to 3D model. I want to learn how to work in these digital ways of thinking. This is art adjacent, or this is creative adjacent.

Then I got through that, and I said, well, a lot of my classmates at the time were getting jobs in the packaging design area. And as a young 21-year-old at the time, I couldn’t think of anything worse than designing a family-size Tide bottle. Although someone has to do it, and someone who likes it is great. As an older adult now, I appreciate the art, the art even within that sort of stuff.

But at the time, I didn’t want a boring job. So I went from there to my first design job. It was a theming design at a themed company in Kissimmee, Florida, right near Orlando. So we were subcontracted by Disney and Universal to make signage—to make themed kiosks—that sort of stuff. I was able to go into a job where I was drawing designs for a snow cone kiosk or a bicycle that when you pedal it makes bubbles, that sort of thing.

Okay. So, a lot of your work that you do, I’m guessing, maybe most of the work that you’re doing is commissioned work. So a brand or a company contacts you and says, we want to do this thing. Is most of that where they have a pretty strong idea about what they want? Is someone coming and saying, "We want Pringles on the sidewalk outside of a Walmart?” And you’re like, sweet, Pringles, sidewalk, Walmart. What happens next?

I work within that whole spectrum. There are some clients that come to me and say, this is exactly what we want. Or we have a picture, please make this 3D.

And then there are clients that come and say, we just want you to work your magic. Here is our brand—make something cool. From there, my approach has changed drastically since when I started versus where I am now. Because at the beginning, I never pushed back on clients. I was just like, what do you want? Let me give you exactly what you want, regardless of whether I thought it was a good idea or not.

Throughout the years, I learned that it was bad for everyone because ultimately, they were disappointed. I was disappointed, and it didn’t end up working out.

You talked about the way this has changed a little bit for you, but you pulled on a thread that I think is really interesting and one I want to spend a little bit of time on. How do you decide what’s a good idea and what’s not a good idea? Both in the context of a client coming to you with an idea, and you’re like, you shouldn’t do that. Or when you start coming up with an idea, how do you figure out what’s going to be a good idea?

I think the best way for me to filter through what I think is good is, am I excited about the final product in my head? Because if I’m excited about it, I believe that other people will be excited about it as well. I think if I go into it and think this seems boring to me, it doesn’t become more exciting to other people.

And so I guess I have to lean on the fact that, I hope that what I think is cool, there will be an audience that also thinks it’s cool. Because if I don’t, then there may be a few that do, but I find that I’m putting less excitement into my art.

When I was a photographer full-time, I used to just tell myself people were paying me for my point of view, right? Like you are hiring me to do this because you want whatever it is I’m going to produce.

Except I also feel like that’s a little bit of a cop-out because they’re also paying you. They are the client. So their point of view matters. And sometimes you have a difference of point of view. And when I was shooting a wedding or a commercial project, those stakes are pretty low because we could always do it again.

It feels like painting the sidewalk at Epcot; it’s still a little bit ephemeral because it rains in Florida occasionally, but it’s a little bit more work, and it’s a little bit more permanent than ‘we could just go shoot this again.’ How do you negotiate that? How do you walk that fine line of sorting through this is the best outcome for everybody?

Yeah. I think I have to drop some of my ego about what I would do in the blue-sky-there-is-no-client sort of world. I like to tell people, especially other artists, that there is a way to only do the art that you love. But it is a very different way than commercial art. It’s very different than commissioned art.

And so I have to kind of put aside my initial, either I’m not excited about it, or I’m not interested in it initially. I have to put that aside and find, okay, now I have this client. For example, there was a client that was a medical supply company. So they provided beakers, test tubes, and equipment for labs for testing for medical companies.

Initially, this company did not excite me at all. There was nothing about it that made me think, oh, this is great. Getting into it more, some of the first initial designs were kind of like, I don’t love this. But within that space of, ‘okay, what about it do I find fun?’ Ultimately, the design that I went with was, ‘what if I painted it like you were very small and trapped inside of a beaker?’ And I could paint it like you’re trapped in this glass and you’re three inches tall and around you are all these medical supplies.

Then you add a little bit of danger, mischief, or things that people can’t stand in normally, to make it add that wonder. Sort of a tangent here, a lot of my 3D designs, I think to myself, what do people want to stand in? People don’t want to stand in a billboard. They don’t want to stand in an ad that is obviously an ad. People want to stand in art or they want to stand in a position that they can’t get normally.

So if you wanted to do a backdrop, and it’s just “Hey, stand like you’re standing in front of our building.” Well, people can just go to your building and stand there. But people can’t balance on a tightrope. Well, most people can’t.

So I usually try to build in either a sense of danger, a sense of excitement or adventure, or a sense that I would never in a million years get the opportunity to do this.

I think the one you’re talking about, I remember the beakers where you’re like inside the beakers, and it’s just a very cool way to do that. And it’s taking something that maybe doesn’t seem as exciting at first and then making it a lot more exciting for people. Once you’ve figured out an idea, walk me through the process of how that idea goes from “this is the thing we should make” to “we’ve made the thing.”

Okay. So most of my ideas, I tend to fall in love with them very, very early, which is a downside to my creative process.

Because you become very attached to that.

I become attached to them, and I think this is the best thing—like, they have to go with this, or this has to be made. And then all of a sudden, the client says, instead of being a 12-foot by 25-foot painting, we now need to shrink it down. And this no longer works because you wanted to put a 3D boat in it or whatever. Now it’s going to be too small.

I go from my idea to the roughest sketches you have ever seen in your life. The kind of sketches that, if people saw them, they would question if I was an artist. They would question if I was an adult. And then they would question if I was an artist.

But those give me an opportunity to throw all these ideas out. And then from there, those ideas can kind of just marinate in the rough sketch world where they’re not very pretty. I haven’t spent two hours on each one. They’re just rough sketches, layers upon layers.

So after I’ve created all these rough sketches and I’m looking at them, these are all my 25 ideas, even though I’m only going to give the client three or four to go off of. Because I believe that when you pare down ideas, you feel like you’re picking your favorite kids. And so I have to do that behind the scenes.

I used to send so many sketches to clients and realize that I overwhelmed them. And out of all the ones I sent, I actually only liked 60 percent of them anyway.

So I realized, this needs to happen behind the scenes. I’m going to present you with my three or five favorites. I think any more than that, you start really overwhelming the client, and you put too much on them, almost by saying, “you make the creative decision.” By doing that, you’re like shedding your responsibility as an artist.

Instead, I want to give you three to five ones that I love. I won’t be disappointed no matter what you pick. And then from there we go to color concepts. I create it with my drawing tablet here, and try to make it look beautiful so that they sign off on that.

After they sign off on that, then I go right from there to, “it’s time to either paint this or put this on the ground.” No surprises because I try to elevate my digital design into a final painting.

So there’s a draft stage where you’re just making sketches, and those are what you’re showing clients? Some version of just like the toddler drew them?

No, “the toddler drew them” scares clients. After the toddler drawings, once I’ve picked my favorite ones, I develop them, but I don’t include color. I think color tends to distract people from the meat of the thing. All of a sudden, it’s like, wait, we wanted that shirt to be yellow, and it’s, it’s red.

So I present them in black and white—like gray scale—with some different line work to show emphasis. But from there, they pick, and then I move into color from there.

Got it. And there’s also the risk that if you show them 17 and they like number 17 and you’re like, “I never want to go anywhere near number 17,” this isn’t worth the money. There’s a risk they become attached to an idea that maybe isn’t the right one, right?

I used to think that I needed to show so many designs to justify being paid for design. It was almost to say, “Look how much value you are getting because I’m producing all these designs.”

But my value as an artist is in my best designs, right? Not the breadth of designs that I can create. Part of my industrial design degree was learning to put in a hundred rough sketches and pick your three favorites from there. So yeah, there’s a little bit of my education coming back to help me.

I’ve found that in different environments where I was managing a creative agency, and we would work with a client, and you want to show them a brand concept that includes logos and colors, and you don’t show them 50, right? You also can’t show them only one because you run the risk of actually, I hate that.

They don’t always know what makes the thing good or bad, but they do know when that’s definitely wrong. So you want to give them a couple of things. How long does that process usually take for you to go from “I’m making sketches” to “I’m showing it to the client” to “I’m putting it on the sidewalk?”

Good question. It varies based on the timeline of the client and how responsive they are in the back and forth. So that can be anywhere from we did this all in a week to, for example, right now I’m in the midst of a design process with a client where I have given them my top three sketches. They said, " We like this one, but with this revision,” and that’s probably going to happen this week.

And then I assume next week we’ll get to, let’s move towards the color concept. So that’s going to be a three-week process.

And how many projects do you have working on at the same time? Is it that you do seven of these a year, and it takes me weeks to do each one? Or, is it the kind of thing where you can be working on multiple projects? I ask that because I think sometimes it can feel like I have too many ideas in my head. I can’t cross-pollinate. Or does that actually help?

I think it actually helps to not be doing the exact same step for different clients. It helps to be at the beginning stages of one while you’re at a later stage of another. Because while I’m doing rough sketches, I’m thinking to myself, man, I just want to be like creating something cool. And while I’m creating something, I just think to myself, oh man, I’m excited to put a bunch of new ideas out there.

And so having things at multiple stages is helpful for me because I like the variety. I think that’s part of my personality. I want to be doing different things all the time, so being able to jump from one to the other actually is great.

You may think that this is because I have kids, but it’s actually probably more about just my personality and how I like things. But I don’t want to be doing design for more than two hours at a time. I think that you get to that point while working on anything.

The exception is creating and painting. I can work for long, long stretches because I’m not making creative decisions along the way. If I’m making design decisions, I can become incredibly negative after multiple hours of working on it. And everything I look at just looks like the worst idea I’ve ever made in my life.

It’s like when you stare at a word for too long, and you’re like, “Is that even a word? Is that real? What does it even mean?” I get it.

Right. Right. You start saying it slow, like horse-rad-ish. Why do we call it a horseradish? Yes. Yes. I totally understand that.

I agree because I can only write for a period of time. And it’s funny because my family doesn’t quite understand that. They’ll look at me and think, “Dad’s not doing anything.” I’m like, no. Part of the process for me is I have to just sit here and think. I’m filtering which idea I should actually write about, and then I can actually write it in maybe 45 minutes. But if an article takes me more than 45 minutes, I’m just gonna be like, forget it. I’m going to find something else.

Yeah. There is something about—I find this in most creative people—there is an intensity that I bring to what is actually a very lighthearted and goofy thing. If you tell someone I’m a chalk artist, it’s not supposed to be taken that seriously. It’s chalk art. It’s what kids learn to draw on.

But just as a creator of something, I get super intense about it, which I used to think was a huge negative. Now I see a sort of balance. There are pros and cons to it. But when I get into work, it becomes super important to me in those moments, which is great because then I shoot for excellence. I’m not willing to just shoot something out and say, okay, that’s fine. I want it to be great.

But, on the other side of that coin, I sometimes get so caught up in that, I need to remove myself from the process in order to come back with fresh eyes. It’s sort of, these don’t have to be the best sketches you’ve ever done. These ideas don’t all have to be amazing. You’ll turn it into something great later down the road. Don’t put so much pressure on yourself. So that’s part of the emotion that goes into the process for me.

Do you feel like your ability to discern what is a good idea and what is a bad idea is a thing that you’ve had all along, or is it a thing you’ve had to learn? The reason I ask is that, in a lot of ways, creativity at its core is less about making a thing than it is knowing what thing to make. And so I’m just curious whether that is a skill that creative people have from the beginning, or is that something that they learn along the way? Either based on education or experience of making things that were good and making things that were bad? I’m just curious how you think about that.

I don’t know exactly if I have a good answer for you on that, because at times I think I have a really good sense of what is good and what is not good. And other times, I think that it surprises me later on.

For example, I think things that are mediocre ideas or not incredibly original or not incredibly like, yeah, novel in any way, when done at a high, high level of execution, become great. I also believe that great ideas or novel ideas, when done hastily or sloppily, can really be ruined almost.

Maybe that’s too strong a word, but it can definitely be that this was a great idea, that you either didn’t quite have the skills to execute, or you didn’t give it enough time to figure out how the idea was going to come to life. I find that’s usually a recipe for disappointment.

Do you find that when you’re putting paint or chalk on the ground or the wall or whatever, it seems to me like you can’t really iterate. It feels like you have to pretty much know going into it what it is you’re going to be putting on the wall. Because I think about how I can polish an article for years. It may not be worth publishing anymore, but I can just tweak the words. At some point, I have to decide, nope, I’m done. I’m moving on to the next thing.

But in your case, I think you have to be done before you start painting. Is that true?

No, it’s actually that I can also work on a piece forever. I can noodle away in a painting or a chalk drawing. To me, I have to step back and say, okay, I know I can make this better, but it is diminishing returns of how much better it gets.

Also, while I would like other artists to be impressed—just like I think you would want other authors to be impressed with what you write—I also want my work to be broadly enjoyed. And thinking of a broad audience also means that the six hours of work that I could add to it might up it by one percent, or maybe nothing, to someone who just looks at it and wants to enjoy the art. I believe it’s Parkinson’s law that you will always expand to fill the time that you give yourself. I always think to myself, I just want one more hour. I want three more hours. I would use it. I’d use all of it. And I would make small adjustments and small decisions, but eventually you have to drop the brush, or at least give yourself a deadline where you have to drop the brush.

Well, you actually touched on a thing I think is really, really important in creativity in general, which is that a lot of people think that you could be more creative, the more time, the more whatever you have. And I actually think the opposite is true. Creativity thrives in restraints. It thrives on deadlines. It thrives with budgets because if you had infinite time and money, you wouldn’t have to be creative. You could just do it all, right? It’s always a series of decisions, and having that deadline and knowing that at some point you have to stop. I feel like that actually is one of the most important pieces of creativity. Is that true in what you’re doing?

Oh, yes, absolutely. I definitely think it’s probably a bell curve. If you have a deadline that’s too fast, then you end up thinking, “I literally don’t have enough time to do this.”

But for the majority of my projects, it involves cutting myself off internally, not even to the client. I try to, if I have a deadline to finish something, I try to give myself at least two hours buffer back from my deadline, so that in my head, I have to trick myself. This is the end of it. Because then after that point, I take a picture of my art and I prioritize what are the three things that I can fix in these remaining two hours. Or what are the things that I can improve?

Actually, for me, 3D art, which is called anamorphic art on the ground, has an anamorphic stretch to it. Everything more than 15 feet down the ground, down the lane is so stretched in the camera that it is almost like those details are almost not seen. They are a pixel on your iPhone. So if I find myself caught out there, out in the great ether of 20 feet away from the viewpoint, working on a detail that no one will see, I have to catch myself and say, nope, you need to prioritize the bottom five feet of your art, which will take up 70 percent of the photo shot.

One of the things I love is that on your Instagram, when you post projects that you’ve done, you post intended perspective, but you also always include what it looks like if you just go off-axis and look at it. It is shocking because it’s so cool.

It’s actually a good metaphor for art in general, that every artist comes to something with a point of view. And that if you view it from any other point of view, it could just look like weird strokes on a canvas. But then, when you understand the intended perspective, it’s pretty cool. So again, I’ll encourage our listeners to check out your Instagram.

A couple of quick questions as we sort of wrap up here. One of them is, what is the hardest thing about what you do? Aside from raising two children at the same time.

Right. That is the hardest thing I am doing currently.

Way harder than anamorphic street art.

I’m going to give myself, I’ll give you three things. Not because I’ve thought of three things, but because I’ve thought of one and I’m definitely going to think of two more.

That’s great.

One, it is a physically taxing career. When you do anything, walking around, painting on walls, crawling around, painting on the ground, it is just a physically taxing thing. A lot of chalk artists and street painters do end up with some form of knee issue from a career of doing it. I hope to be able to do it for a long time, but I also know in the back of my head, I want to transition over time to doing less on-the-ground work just because the body can’t keep up with it. So that’s a sombering and yet a real issue with it.

How long, I mean, just while you’re saying that, you can still think of your other two, but how long are you typically painting a project?

If I’m doing something on the ground, it’s probably three to four days. If I’m creating a mural, that can be several weeks to a month for a more permanent one.

So when I say mural, I mean more of the permanent art versus anything that is a marketing, ephemeral chalk art or tempera paint, which is a temporary paint. All of that is usually done for an event, and typically, you’re not able to have access to a space for more than two to three days before the event rolls into town. On the side of a building, you can get out there three weeks earlier.

The second thing is that the art that you create primarily doesn’t last. As a chalk artist, that involves a bit of an ego hit or a bit of the acknowledgement that when someone says, “Oh, you’re an artist, have you done anything around that I can see?” No, no, I haven’t. All of my work has been washed away by now, which in some ways is maybe one of the best things for me because it does keep you humble in a way. I have a few murals here and there, but for the most part, go check out my Instagram. If you want to see it, it was there, and now it’s gone.

Oh yeah. That would be tough. What, as far as the creative process, though, is there a part of that that you struggle with the most? Is it, is it hard getting clients to agree? Is it hard to get ideas out of your head? Is it hard to color? Like, is there a part of that? That’s a challenge.

I would say, which is actually going to be my third one. So you, you hit it. Exactly. The hard thing is working with big clients with big budgets, trying to convince them to do creative, exciting things. It tends to be smaller projects are usually smaller clients are much more willing to like, let’s try something fun and cool.

There is a more conservative approach creatively with bigger companies because we have a brand package you need to stick to, and we aren’t sure if we can do something. For example, I talked earlier about wanting things to be dangerous or exciting when you pose in them. What if you’re a company that’s like, actually, we don’t want anyone to show themselves doing something dangerous or not safe?

All of those things are really hard to thread the needle of. This needs to work for the client. I don’t blame big clients for not taking big swings, but it has to get to the point where there’s fun remaining inside of it. I spend a lot of time pushing clients. Please don’t put that many words in this art. Please don’t put a slogan in there. Please don’t put hashtags in there. I mean, maybe your logo, but please make it a cool logo.

This was a huge trend in the past 10 years, where everyone wanted to put hashtags in 3D art, which is not how hashtags work. Your phone doesn’t read that and say, oh, I’ll log this. So a lot of it is trying to convince clients that people don’t want to stand in an ad and advertise for you. They want you to be the sponsor of cool art. They will like you as a brand. They will like you as a company because you created something cool for them. All of that convincing is probably the hardest thing creatively.

Yeah, I’m looking at like the McLaren one you did right now. And there is a pavilion behind it with the McLaren and the Dell logo. But thankfully, they didn’t make you put the Dell logo in the artwork. That would be a challenge.

But that’s an example of a specific job where it started as maybe it could be something Dell, very McLaren-y, like very brand heavy, that turned into what if we just use the colors within the structure? What if we use the track, but we’re playing up the Dell blue that we have a color code for that we could use for it. But those are all negotiations internally, of, hey, we want this to be great. We want the fans to enjoy it, but we don’t want this to get in the way of people’s enjoyment.

A couple of quick ones to finish up. What is the thing you have made that you’re the most proud of? Or is there a project you worked on that you love the way this one turned out? Everyone should go look at that one, because that was the best example recently of a project that I’m just super proud to have made.

Yeah, I have quite a few that I am proud of. Recently, I worked with a company, an organization for people who are coming out of incarceration. And the Dismas House, which is a local place in South Bend that helps people get back on their feet after incarcerated.

I did a mural for them recently, and everyone in the mural is a real person involved in the organization or in the house. And so it was a crazy challenge of trying to depict real people in this mural. I think I ended up with maybe 28 people in it altogether. I’m very proud of that. That happens to be one of my more recent ones. But then I have other ones that I feel like I like jobs for different reasons, and I dislike them for other reasons.

It’s not so much that one job is good and one job is bad; I really thought the 3D element of this particular thing works really well. For example, I did an Indiana Jones one of him crawling down a rope into the ground at EPCOT this last year. I was really proud. I put a lot of extra work randomly into the rock edge of the hole. And because of that, I was very proud of the 3D hole in the ground, which is a very cliché thing for 3D artists to do. But I was happy with that execution.

For example, for Riot Games, we did a big dragon. I loved the subject matter. We did a Kobe mural, myself and another artist out in LA for Nike. And I thought the Kobe likeness was really great. I was really proud of my work on that portrait.

If you give it more than a year, I start looking back on it and think, oh, I wish I could do that again. I think I’ve improved since then. But I think everything’s got a little bit of an element to it.

Okay, last question. What do you do that is not chalk art to sort of hone your creative skills? Do you have a different kind of hobby, or are there other things that you do creatively that you feel help make you just more creative in general?

I have a million hobbies that I don’t get to as much as I would want to. I think if someone were to be personality typing me during this interview, I’m sure you could figure that out by now, that I have quite a few things that I love to try out.

I have been recently tinkering with doing hand-drawn animation. I’ve always wanted to be an animator. I don’t really see that as ever becoming an income thing or a career thing, but I like the idea of making things animate. So that’s something that I’ve doodled around with recently, sort of in the art world.

I love playing board games. That’s a big hobby for me. Behind me, I have a piano. So I will play around a little bit, try to get better at that. So creative adjacent things. And then woodworking is something that I’ve started doing recently. Just trim work in the house and some DIY stuff there. But that gives me a feeling of being very specific. It’s kind of LEGO construction for adults. I like following directions or making something exact.

The downside to a fine art career is that it’s all a little squishy. It’s a little subjective. It’s a little subjective versus having a really tight joint—you either have it, or you don’t.

I think working that analytical side of my brain, you know, doing a crossword, doing woodworking scratches that itch.

I also had one more thing I wanted to say because I would kick myself if I didn’t say it on this. My workflow has been—for the past two years—completely changed by the use of VR.

Okay, say more.

Before now, I have used the grid method or the doodle method to put my designs onto a ground. So if I have a 20-foot-long piece, I either have to grid it out, draw it out from there, have grids on my reference paper, and go from there. Or I have to use a projector, which is hard. Because when you’re projecting on the ground outside, you either have to do it at night or a projector has a focal length. And because you’re projecting it down at an angle, you only have one thing in focus at a time.

But I had a VR headset, a Quest, and I said, “Oh, they have programs where you can project your image onto a wall for creating a mural.” And then you can adjust the opacity so that you can see, and you’re basically tracing your image. I said, why can’t I apply that to the floor, have my image already stretched out.

From there, I’m able to take my design that I worked hard on on the computer, load that JPEG into the headset, and from there, I’m able to project my design perfectly on the ground, lock it into the area.

So for the past couple of years, I’ve been using a headset to project my initial lines, and I think you could almost see the jump in detail I was able to put in, probably around two summers ago. It has really made the laborious part of transferring a piece of art to the ground—I can now rush past that section, or at least get through what used to take a whole day now takes me an hour. So now I can spend all that extra time filling in and doing the rendering work where is fun for me.

Yeah, I definitely noticed two summers ago that your work got significantly better.

Perfect. Perfect.